RetroCast and SynthArena: building the infrastructure for the next breakthrough in chemistry

December 14, 2025 · Anton Morgunov

TL;DR for ML Researchers

Current SOTA in chemical synthesis planning is rewarded for generating chemically impossible routes due to flawed metrics (pseudo-solvability) and dirty datasets. We release RetroCast, an open-source framework to standardize evaluation, and SynthArena, a live leaderboard to enforce accountability.

TL;DR for Chemists

The common "solvability" metric for retrosynthesis models is blind to chemical validity. We show top models proposing nonsensical reactions (e.g., a 7-component glucose synthesis) that are counted as successes. Our tools allow for rigorous, apples-to-apples comparison of synthesis plans.

TL;DR for the General Public

AI that designs chemical recipes is in its wild west phase, with models claiming success for impossible plans. We're building the "ImageNet for chemistry"—a set of fair tests and a public leaderboard to bring order to the chaos and find what actually works.

Imagine you're a chemist trying to create a new life-saving drug. Your first question is: "how do I even make this?" The process of designing that chemical recipe, working backward from the final product to simple, buyable ingredients, is called retrosynthesis. It's a puzzle so complex that became a grand challenge for AI.

The problem? The AI community has been keeping score with a broken ruler.

The so-called "solved" route

I rerun major open-source models on a commonly used set of 190 targets (called USPTO-190would you be surprised if I told you that it's nothing more but a test set of Retro* paper, which was constructed such that every single-step reaction in the reference route was within the top-50 predictions of the single step model, i.e. it was constructed to ensure Retro* succeeds on this set of targets.) using a more sensible choice of starting materials (300k molecules curated by a leading group from MIT), and the results are spectacular. Here are the top-2 performing models.

| Model | "Solvability" | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Retro* | 73.2% | [66.8, 79.5%] |

| AiZynthFinder Retro* | 36.8% | [30.0, 43.7%] |

where AiZynthFinder is a more recent retrain of A* model by researchers from AstraZeneca. Judging by "solvability", the dominant automated metric in the field, original Retro* is a clear winner. However, let's inspect a few predictions that are considered "solved." As shown in the figure below, one "solved" route (panel A) involves construction of glucose through a 7-component reaction. If you're a chemist, you're probably laughing hysterically. It's not creative or risky, it's simply impossible. Why would it count as a solved route? Because "solvability" is a misleading term masking nothing more than stock-termination rate, i.e. if all terminal molecules are in the stock set.if you're a chemist and you're wondering how such nonsense became an accepted practice, see section with historical context below

Why would Retro* offer such a non-sense reaction? Well, as it turns out, the reference route from the USPTO-190 (Panel B) contains EXACTLY the same reaction (whole route differs only in the first few reactions from target). A newer model like AiZynthFinder doesn't make such nonsense suggestion (Panel C); it struggles to find a valid route and this target overall is unsolved. Panels D-H are a few more examples of even syntactically incorrect reactions.

By the way, another contribution of the work is a common platform for visualization of routes—SynthArena. You can inspect referenced routes by clicking these links: USPTO-082, USPTO-114, USPTO-169, USPTO-93, USPTO-16, USPTO-181.

It might be tempting to ask, well, what if you cherry picked these examples? One—these are only syntactic failures, i.e. these are undisputable failures, a model can also propose reactions that at least are structurally correct, but may be experimentally unfeasible. Two—it doesn't even matter. Existence of these examples is enough to make stock-termination rate (STR) a metric that you can't trust without visual inspection. So any claims about model superiority, on this dataset or any other, based on STR alone are meaningless unless you have a chemist who would manually inspect every route to make sure it's sound.

How did the field come to tolerate this?

Reading the section above might leave you incredulous: you must be hyperbolizing, Anton, how come the whole field seems to have gone insane? Any chemist would tell you that stock-termination is insufficient to call the route "solved." And yes, major chemistry-by-origin playersProf. Connor Coley at MIT, a research team from AstraZeneca, Dr. Marwin Segler at Microsoft, Prof. Philippe Schwaller at EPFL know that, so their papers either acknowledge this caveat or accompany evaluations with manual inspection by human chemists. However, numerous contributions (including the Retro* paper) came out of CS groups, you'll often see papers on retrosynthesis in pure ML conferences, and so for unfortunate historical reasonsfeel free to skip the section if it's too long for you, "solvability" became a metric demanded by Reviewer 2.

A field adrift: how did AI-driven retrosynthesis get here?

After AlphaGo's spectacular success, Segler, Preuss and Schwaller wrote a beautiful landmark paper, applying Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to the problem. Here's the basic process of MCTS:

- You have one neural network that takes a molecule as an input and returns a set of prioritized reaction templates/rules (say 50 out of 100k in your library) by which you can make that molecule.

- You apply those templates to your product and obtain 50 candidates of reactants.

- You feed each (reactants, product) pair into a different neural network (feasibility filter) that tells you if that reaction can happen or not.

- You perform a rollout to estimate which of the remaining reactants are most likely to lead you to the commercial starting materials, which allows you to ignore certain branches and thereby reduce search space.

- You keep doing until you run out of time or all your terminal molecules are commercially available

A target was determined "solved" if the procedure found a route, i.e. all terminal moleculeswe call them leaves, a term from graph theory were commercially available. Now, strictly speaking, just ensuring all your leaves are commercially available is not enough, you also need to make sure that the reactions by which you transform those leaves into the root nodethe target molecule you started search from are all syntactically and semantically correct. The feasibility filter (step 3) was supposed to ensure that.

How did they get that oracle? They took a huge database of reported reactions (10 M examples from Reaxys), for each example (reactants, product, reaction type) took all reaction rules other than the reaction type reported, applied them to reactants, and if the resulting product was not recorded in the original database, then that was considered an example of an impossible reaction.in other words, they created synthetic data for negative examples A feasibility filter was trained as a binary classifier of positive and negative examples.

The MCTS paper was published in Nature, so naturally it attracted a lot of attention to retrosynthesis. Two years later, a CS group from Georgia Tech published an application of A* search with neural network acting as the heuristics value function to the problem of retrosynthesis. The benefit of resulting Retro* model, in theory, was better efficiency since you don't need to do expensive rollouts. Being a CS group, however, they overlookedor deliberately made a particular design choice a critical chemical aspect: Retro* didn't incorporate the feasibility filter (like step 3 of MCTS). Maybe because they assumed a single step model that suggests relevant templates can also learn the rules of feasibility because it operates on the same information.i.e. product structure and implicitly structure of reactants, since that is determined deterministically by reaction template Maybe they just couldn't train a good feasibility filter with the data they had. Regardless, they considered a target solved if the model found a route with all terminal molecules being commercially available, without any checks on the feasibility of transformations connecting those terminal molecules to the original target. What's worse, instead of using a realistic dataset (400k) of molecules that are truly commercially available (you can buy them here and now), Retro* used an eMolecules made-to-order virtual library of 230 M molecules.eMolecules is not exactly a vendor of molecules, it's a CRO, i.e. they're willing to perform a few steps of synthesis from the off-the-shelf 200-400k set to significantly expand their offering

Note

The database used in MCTS paper, Reaxys, is proprietary. Retro* was trained on the only free source of chemical reactions--the USPTO (p - patents) database that contains ~1M reactions. The implicit assumption in the generation of synthetic negatives in the MCTS paper was that the database of positive examples is comprehensive; such assumption is much more likely to hold for Reaxys (which is what experimental synthetic chemists consult in their day-to-day) as opposed to USPTO.

Retro* was published in ICMLa very prestigious ML conference, so it solidified retrosynthesis as a problem that can be tackled with ML, and we ended up with 5 years of publications in which the target was considered solved merely after checking if terminal nodes are in a stock of 230 M molecules,it's quite ironic that a model that is supposed to propose synthesis recipe is considered succesfull if it ends in molecules that themselves need to be synthesized without any explicit checks on the validity of chemical reactions in the final route. In other words, the field of retrosynthesis has been adrift ever since.

There were a few attempts to course correct. One of the key players is a group of researchers from AstraZeneca, and they constructed a very cleanthe full USPTO-1M is notoriously dirty dataset of multistep routes and published 2 evaluation sets, 10 000 targets in each with known experimental routes, and proposed to assess retrosynthetic models based on the ability to find that experimental route for a previously unseen molecule. This benchmark, PaRoutes, has gained some adoption, but unfortunately it's not universal. I saw two obstacles:

- Even with the cheapest search method, full evall will take hundreds of CPU hours, so if you have a more powerful (and a more expensive) method, well do you really want to spend potentially $1k in GPU hours on a single eval?

- There's no standard agreement on how a multistep route should be represented. Some methods store them as recursive unipartite dictionaries, some create bipartite graphs, some create stringifed maps. If you want to compare predictions of different models, you have to write custom code for comparison of each one with the experimental route.

So I built a toolkit for sanity

To fix this, I built a unified infrastructure. It starts with RetroCast, a universal translation layer with adapters for over 10 models that casts all outputs into a single, canonical format. This solves the "babel of formats" problem and enables true apples-to-apples comparison.

On top of this, I created a new suite of smaller, stratified benchmarks by sampling the excellent PaRoutes dataset. This provides high diagnostic signal at a fraction of the computational cost, revealing how models perform on routes of varying length and complexity.

Like I argue in my recent longread, computational science is constrained by infrastructure, not ideas. RetroCast and SynthArena is my inaugural contribution towards better infra.

SynthArena

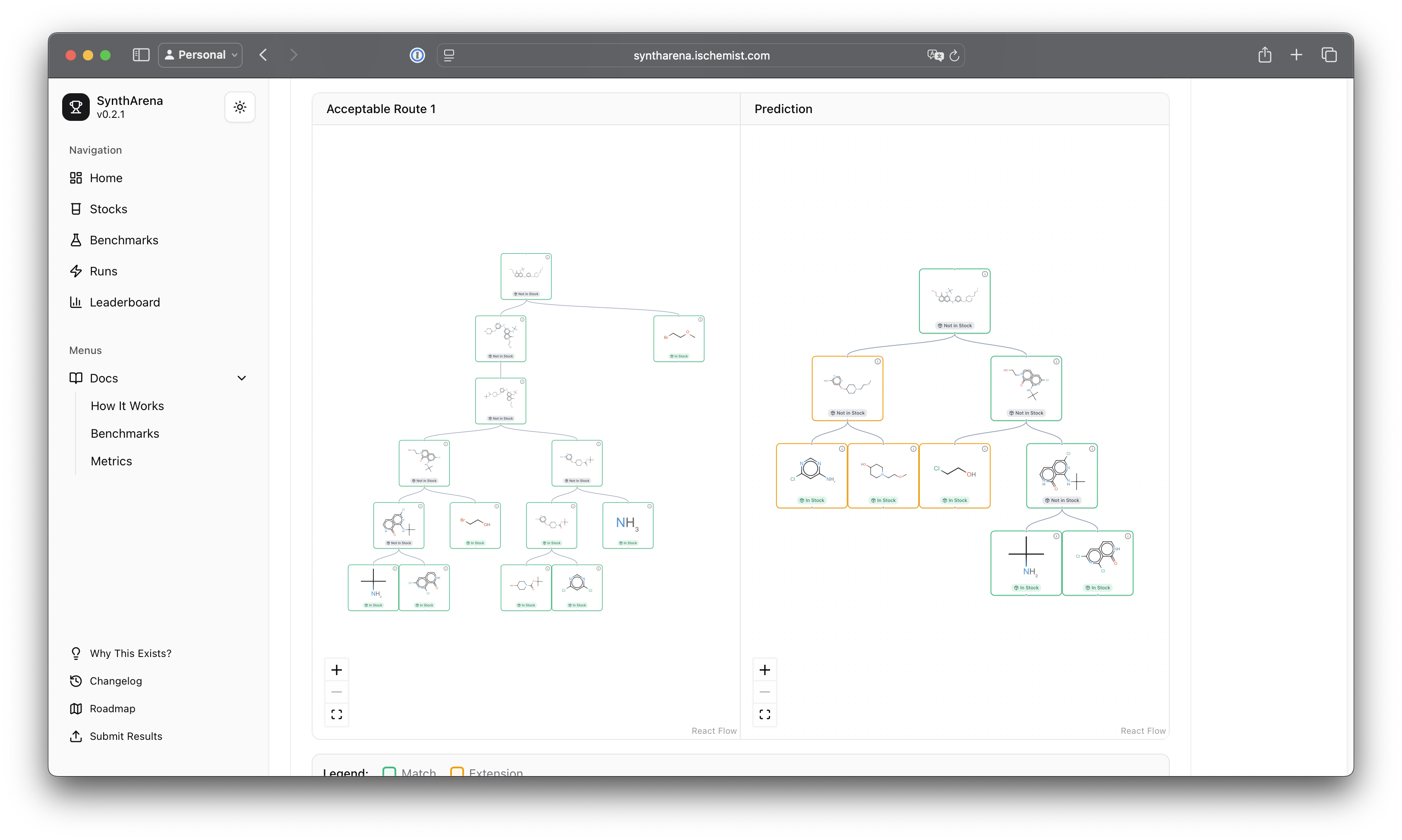

A picture is worth a thousand words, so here's a side-by-side comparison of experimental route (left) to predicted route (right):

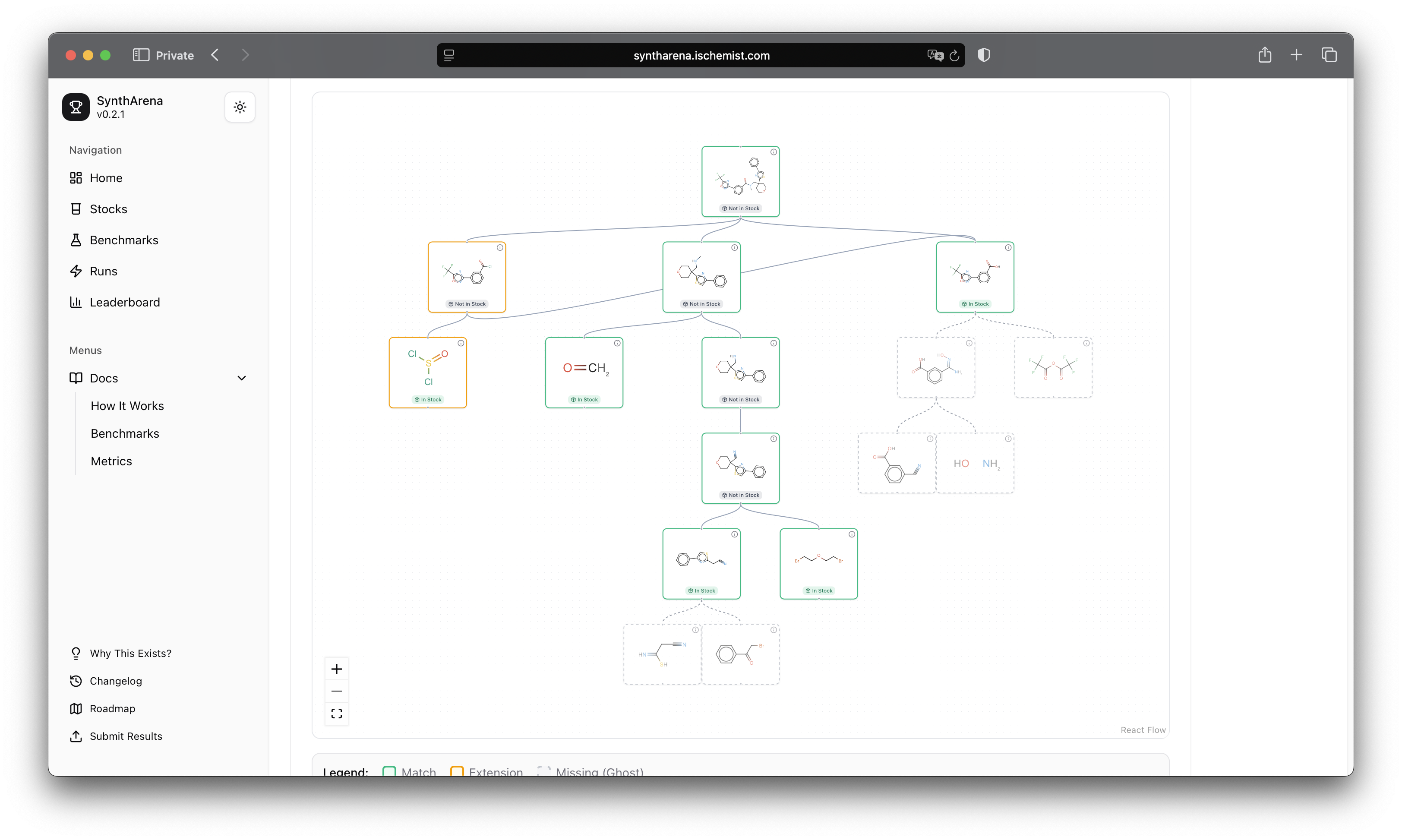

and here's an overlay view:

Why this is more than just a tool

At some point, I started to wonder if I'm allocating my time right—is retrosynthesis problem worth all this effort? In the process, I formulated a coherent argument why I believe ML for retrosynthesis is yet to have its moment of fame. Long story short, all major successes of AI so far were on structural (as opposed to quantitative) problems, and retrosynthesis is one of the few structural problems of chemistry. You can read full argument here, which is, together with RetroCast and SynthArena, is probably my love letter to the field. It's been underattended and underappreciated, and I hope I'll push the needle.

Beyond the Paper: Meta-Lessons

Data flow is everything

One key meta-lesson I learned in the process of creating both RetroCast and SynthArena—data flow is everything. 90% of the good workflow is the right choice of data representation, from that everything, including code quality, follows. How do I get data representation right? Unfortunately, I don't have a magical recipe, but it's just something I learned you have to pay the most attention to. It helps to explicitly write out the vision for the whole intended workflow, from start to finish. For example, before even beginning to write the code for adapters, you can try to sketch out whole ingest, score, analyze workflow to see what would be the best way to represent data to support all of them.

Coding solves the epistemological cringe of classical confidence intervals

I knew that confidence intervals existed since my freshman year when I took my first lab module. I knew the classical derivation: you normalize your values around mean and standard error, then you multiply it by 1.95 which is some coefficient that comes from some Student'sthere's a hillarious lore behind it btw, Student is a pen name of William Gosset , who developed the ideas while working on quality assurance of Guinness (yes, the beer) t-test. And I could understand each individual math stepthough I still have hard time internalizing the concepts of dividing variance by vs , or both, I never internalized the intuition and it seemed to rest on an assumption that you have large enough number of samples for all the convenient theorems like "errors are distributed normally" to kick in. So I never used confidence intervals in my actual research. Until I learned about bootstrapping, which is really just writing code to resample measurements with replacement, and calculate the percentiles of the distribution. No assumptions about normality, no magical coefficients, just the literal definition of a confidence interval.

Access & Citation

that's all for today, hope i made you curious enough to check out the paper (or at least the figures).

Cite As

@misc{retrocast,

title = {Procrustean Bed for AI-Driven Retrosynthesis: A Unified Framework for Reproducible Evaluation},

author = {Anton Morgunov and Victor S. Batista},

year = {2025},

eprint = {2512.07079},

archiveprefix = {arXiv},

primaryclass = {cs.LG},

url = {https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.07079}

}